Charlotte Faubert- Architecture in the Qingming Shanghe tu Scroll

Architecture in the Qingming Shanghe tu Scroll

The Qingming Shanghe tu Scroll, sometimes referred to as the Peace Reigns on the River or Spring Festival on the River scroll, is a handscroll on silk with ink and color that extends to be approximately thirty-seven and a half feet in length. This scroll is an incredibly important emblem of ancient Chinese art, and it has been replicated by master artists many times throughout Chinese history. The work is attributed to Zhang Zeduan, though this is heavily debated, and it was commissioned by the Imperial Court of China by order of the Chinese Emperor.

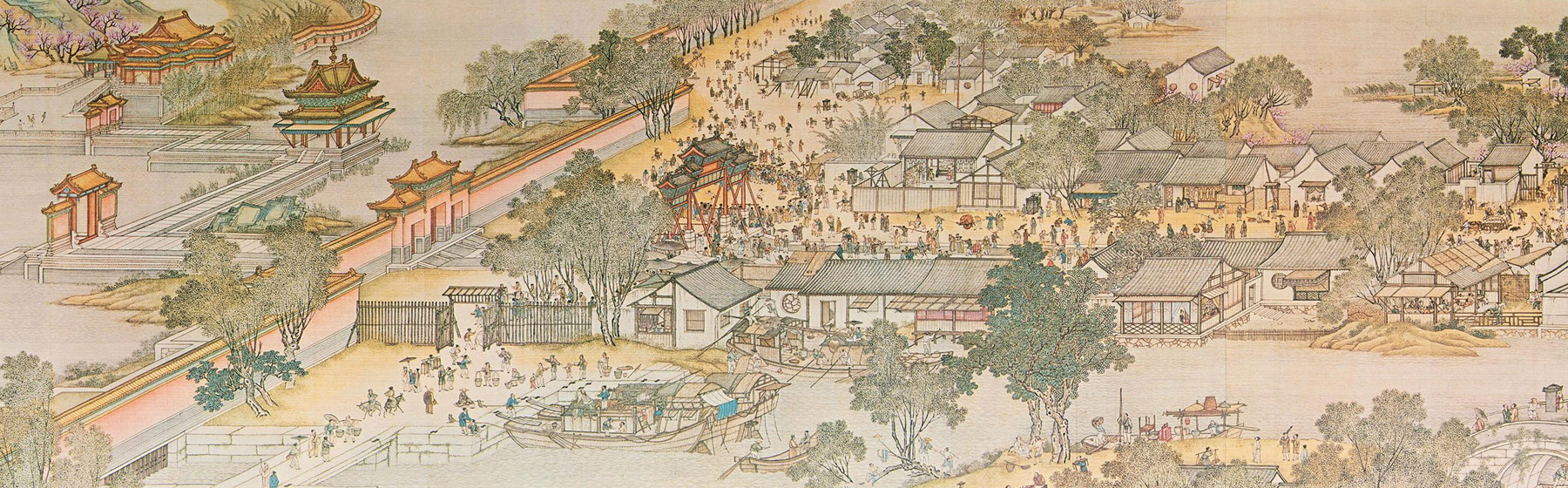

There are a multitude of visual and artistic aspects that appear throughout the scroll and capture the viewer’s eye. One facet of the work in particular includes the intricately drawn buildings and architectural structures. During the Song Dynasty, structures were painted using a technique called ruled-line painting, otherwise known in Chinese as jiehua. The goal of ruled-line painting was to create precise, proportionally accurate recreations of Chinese buildings, bridges, and vehicles. The techniques employed in creating the architectural structures in this handscroll are reminiscent of this ages-old painting form. Take, for instance, the wall at the entrance of the royal court in section twelve and thirteen of the scroll. The angles and edges of the structure were meticulously created to appear as straight and realistic as possible. The detail in the scaffolding on the wall, as well as in the roof over the entrance to the royal gardens, are especially impressive. The fine detail and line-work on these formations emphasize the extravagant architectural design of the structure, and the extravagance and beauty being shown establishes this structure as a part of the royal court. Other buildings in the city, like the small houses just outside of the royal palace border wall, are also drawn to be as life-like as possible. The line work on these buildings reveals the texture of the roofs’ material, and we see the same intricate lines on the fencing surrounding these homes. The ruled-line technique has strong ties to another important art form in China called calligraphy. Many scholars agree that traditional Chinese painting rules and methods were formed off of the basic building blocks of this form of writing. An article entitled “The Influence of Chinese Script on Painting and Poetry” reflects on this idea and states that “Chinese art criticism is heavily dependent on concepts and terminology developed first in relation to writing and later adapted to painting” (Wachtel and Lum, 1991). The principles of calligraphy developed both the painting style and the skills required to be a masterful artist. Calligraphy involves using a brush dipped in ink to write Chinese characters. While this may seem insignificant, it is a highly celebrated form of artistry because of the methods used in creating the characters. The use of line work is the main component in calligraphy, and the smallest details within the line, such as its length, the changes in its thickness through the application of pressure to the brush, and the way it intertwines with the other lines in the character, are perfected over many years of practicing and copying the calligraphy of the masters. The mastering of calligraphy is a high honor and indicates years of hard work and dedication to the practice. That being said, line work comes into play in many areas of this hand scroll, and in particular the architecture requires a highly experienced artist to replicate the straight edges of buildings and other structures.

Another way in which the linework on the buildings and architectural structures throughout the scroll successfully portray a realistic scene of life in China is by creating three-dimensional depth. An article examining the way in which Chinese art is classified by art historians points out the lack of acclaim for the realistic and three-dimensional representations of architecture in tenth and eleventh century Chinese art. Hong writes “...when Western art historians applaud the expressionistic accomplishments of later Chinese literati painting, they ought not to ignore the fact that before then, from the tenth to eleventh centuries, Chinese painters had successfully conquered the illusion of a three-dimensional space in the representational art.” (Hong, “James Cahill and the Study of Chinese Painting”, pg. 4). The overlapping set up of buildings in the scroll, such as those in section twelve of the scroll, creates space that stretches back to create a wider, more dynamic field of view. The buildings near the top are created smaller to create the illusion that they are situated further back in space, and this brings depth and realism to the scene. The same phenomenon occurs in the image of the elevated pathway just beyond the entrance to the royal gardens. The structure is created using lines that grow shorter and narrower closer to the top half of the scroll, and this again creates distance within the image. The directionality of the lines, their precision, their length, and their texture all work together to create the incredible, three-dimensional image we see on the scroll.

Works Cited

Hong, Zaixin. “James Cahill and the Study of Chinese Painting.” EBSCO, 1 June 2014,

https://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0.

Wachtel , E., and C.M.K. Lum. “The Influence of Chinese Script on Painting and Poetry.”

EBSCO, 1991, https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/command/detail?vid=10&bdata=Jmxhbmc9amEmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZl.