Julian Lightburn - Chinas Grand Canal

Grand Canal in Ancient China

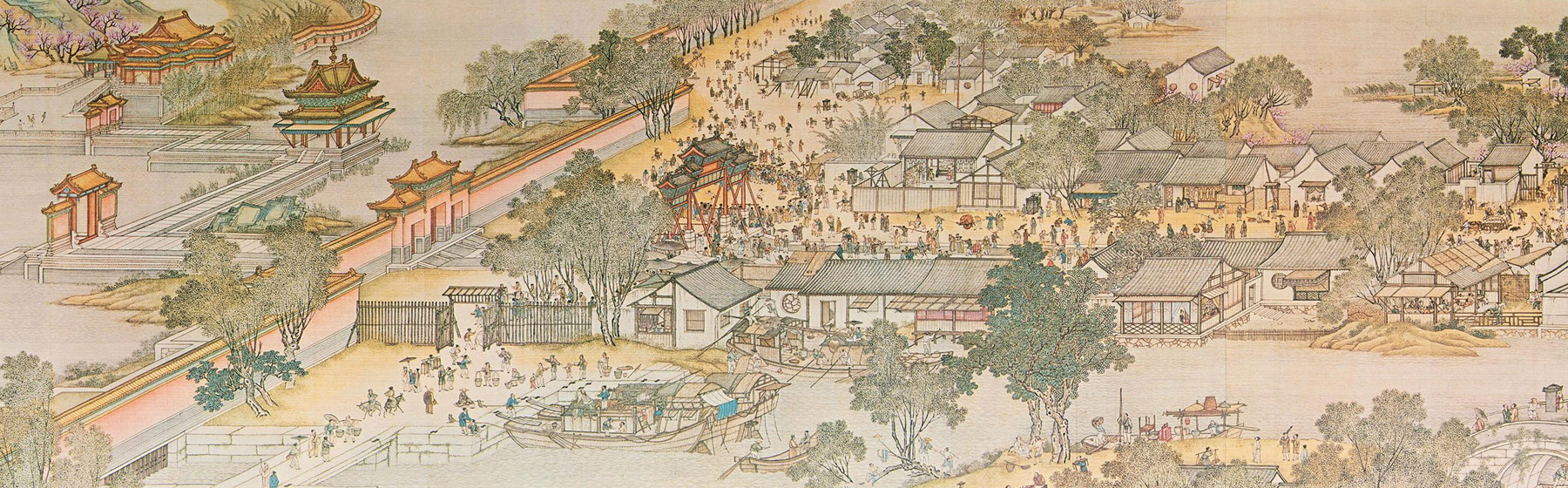

This handscroll is broken up into 3 main sections. The first of 3 represents the lower class of individuals given the lack of architecture and shops. As the scroll begins on the right hand side, the landscape begins with a farm along with accompanying farmers and cattle. As the scene begins, there is a large emphasis on water. The grand canal, dug as early as 486 BC, started the relationship between the rise and falls of cities based on the functionality of the canal. “In ancient China, the rise and fall of cities and regions were closely related to the canal” (Huang et al., 2021, p. 1). Impressively the grand canal is the first and longest canal in the world (Huang et al. 2021). The success of the cities greatly depended on their proximity to and usage of waterways. The usage of space in Chinese scrolls along with the representation of subjects guide the eyes intently throughout. The importance of water is being introduced because of the close proximity to the farm. The farms located by the Bian river contain very fertile soil which could aid in the prosperity of the Qing. According to Huaung, “there are loose soil, several lakes, criss-cross rivers, and abundant underwater resources that are suitable for growth.” The seasons in China often dictated the way in which the land was used. During the flood seasons, “water was discharged from the lakes and ponds, which caused waterlogging” (Tan et al. 2019, p. 37). This land that was flooded was great for farming which could be seen on the beginning part of the Qingming scroll.

Moving leftwards, further away from the farmlands there are a multitude of homes that begin to show. In contrast with the farmlands, these homes are pictured to be further away from the water and more inland. The topography of this area seems to be fairly mountainous with a flat area more inland allowing for families and pets to play and congregate. Topography will reveal itself to be a key determining factor in how the rivers and canals were shaped. The makeup of the land near the Bian river consisted of, “mountainous areas, plateau basins, hills, and plains account for approximately 33 percent, 26 percent, 19 percent, and 12 percent of the total area of the country, respectively” (Tan et al., 2019, p. 2). The shape and location of these mountains “determine the direction in which the rivers flow” (Tan et al., 2019, p. 2). Along with the mountainous regions pictured, the trees in the farmland areas seem to be less healthy than those that appear later in the scroll. There is another farmland pictured to the left of the houses that is also close to the body of water, emphasizing its fertility. The inhabitants of the first section of the scroll sustain themselves off of this land and waterways that surround it. This could prove to be the backbone of the city given its lush resources and fertile lands.

Water management was also very important during this time given that heavy rainfalls and arid seasons forced the Chinese to control water. The climate in China from north to south varied greatly. Due to the changes in rainfall, wet and dry seasons, and the variation in topography, the grand canal relied on neighboring ponds and lakes to regulate water flow. During the more arid seasons, spring water was the main water source for canals in the area. These facilities were so vital to the people of the Qing dynasty that the regulation was overseen by the government. “People who took water from the springs of Shandong, Nanwang Lake in Jining...or from water sources in Gaojia Dam and Liuwanpu in Huai’an Province without permission would receive heavy penalties” (Tan et al., 2019, p. 37). During flood season, water was discharged from the lakes and ponds, which caused waterlogging. The floodplains of the lakes and ponds were good places for agriculture cultivation, which meant a conflict arose between water storage and the usage of land for arable farming.

The success of neighboring cities near bodies of water greatly depended on the use of and functionality of canals. Although it is not explicitly stated in the Qingming Shanghe Tu scroll, it can be observed that water played an important role in the Qing dynasty. Being that the scroll is presented in a horizontal format, the river actively conjoins the more suburban areas to the metropolitan city by way of the Grand Canal. Beginning with the more rural areas and farmlands and slowly transitioning to more urban areas shows the horizontal flow of goods and people. The positioning of each of the 3 main sections of the scroll brings our eyes leftwards down the river. The rise and fall of the cities who surround the canal greatly depended on the function of the canal itself.

Bibliography

- Johnson, Linda Cooke. “THE PLACE OF ‘QINGMING SHANGHE TU’ IN THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF SONG DYNASTY DONGJING.” Journal of Song-Yuan studies 26, no. 26 (1996): 145–182.

- Huang,W.;Xi,M.;Lu,S.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Rise and Fall of the Grand Canal in the Ancient Kaifeng City of China: Role of the Grand Canal and Water Supply in Urban and Regional Development. Water 2021,13,1932.

- “The Technical History of China’s Grand Canal.” ProtoView. Beaverton: Ringgold, Inc, 2020.