Max Martirano - Symbolism of Gardens and their Importance

Symbolism of Gardens and their Importance

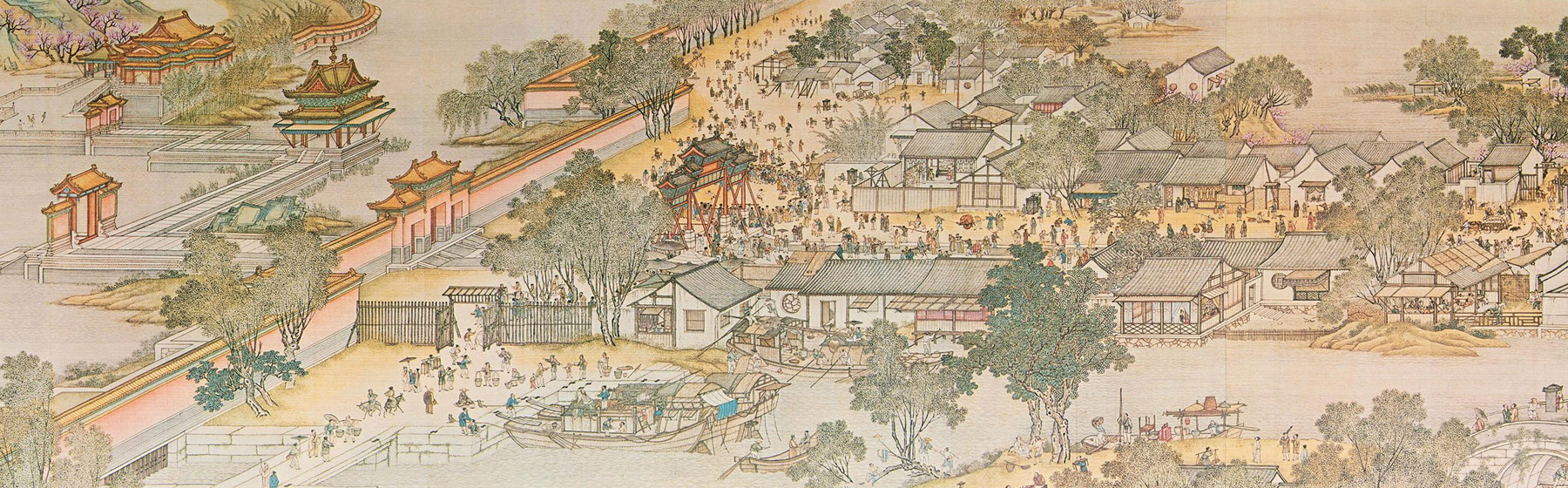

The Qingming Shanghe is a painted handscroll established during the Qing Dynasty in China. Court painters created the Qingming Shanghe that the Zhang Seduan inspired during the 12th century. This handscroll remains a critical piece that depicts a significant snapshot of life through many different landscapes across the dynasty it was created in (Qing). The Qingming Shanghe is over 17 feet in length with an abundance of meaning and critical fragments that help illustrate what life was like during the time. I will be focusing on sections 12, 13, and 14 from the digital collections link provided to us in class.

The scroll in its entirety can be divided into multiple sections that can be attributed to seasons; winter, spring, summer, and fall, which is clear based on the trees withering or perking in the background. At the beginning of the scroll, we see an extensive countryside where hills are seen in both the foreground and background, with the canal sitting in the middle ground. As we continue on the scroll towards the middle, the viewer gets more of an urban presence as the fields are met with a bridge that slowly leads to the first wall where an overwhelming amount of people and merchants reside on the other side. We start to see urbanization arise as this level of civilization appears to be more advanced/popular. Lastly, the viewer is again met by a wall that holds yet another form of life on the other side. This is where sections 12,13, and 14 reside and where gardens and more advanced architecture can be found. While all sections are important and rather clear in the division, through a wall or bridge, I find the latter section regarding the gardens and most advanced urbanization to be the most interesting aspect of the scroll.

In sections 12, 13, and 14, we see the transformation into yet another facet of life during ancient Chinese times. Unlike the previous sections, where the abundance of merchants and overall crowds/chaos control the piece, this section provides a more mellow/calm mood. It is clear from the beginning that the architecture and vegetation have changed as the walls/buildings as well as the plants appear to be both structurally and aesthetically advanced than that of the previous sections. The buildings are more isolated as they are further apart and, at times, on their own island. The structures are encompassed with gorgeous greenery where few individuals are seen admiring it. In these sections, the presence of gardens is quite clear. Throughout the sections, the viewer is exposed to a lot of different plants in the form of flowers and trees that help bring a colorful presence around the landmarks. Gardens play a very symbolic role in Chinese tradition as they provide a mental and spiritual refuge. Aside from the fact that gardens are aesthetically pleasing, they are also an art form seen in ancient Chinese dynasties. Creating a visually appealing garden is like composing a well-written verse of poetry. It is necessary to achieve the proper twists and turns and the resonance of beginning and end. A proper garden is like telling a story that depicts both the area in which it was composed to the composer themselves. In this painting, it is clear that the gardens/atmosphere provide peace and security that concentrate that energy outside of the walls. This feeling of peace and harmony is only proper at the end of the scroll to parallel that to the end of a story. (Li, Wai-yee). Much like the entirety of the scroll, ancient Chinese gardens were not meant to be seen at one time, rather an overview into many different aspects of life. Whether it be a look into a pond or a rock or pile of bamboo, all are evident in these three sections. As seen throughout the scroll, the hustle of daily life is evident between merchants and farmland in the previous sections. However, in sections 12, 13, and 14, the viewer is given a break from “normal daily life” as the gardens provide refuge from the intense activity that remains outside the walls. (A Chinese Garden Court)

Bibliography

LI, WAI-YEE. “Gardens and Illusions from Late Ming to Early Qing.” Harvard Journal of

Asiatic Studies, vol. 72, no. 2, Harvard-Yenching Institute, 2012, pp. 295–336, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44478263.

Murck, Alfreda. “A Chinese Garden Court.” Google Books, Google.