Brett Miller

Qing Market Structure

Throughout Chinese history, recreating works of famous historical artists has been a common form of art, demonstrating respect to renowned masters. Many copies of older works contain revised scenes with subject matter relevant to the times they were created in, while still maintaining the basic composition of the original.

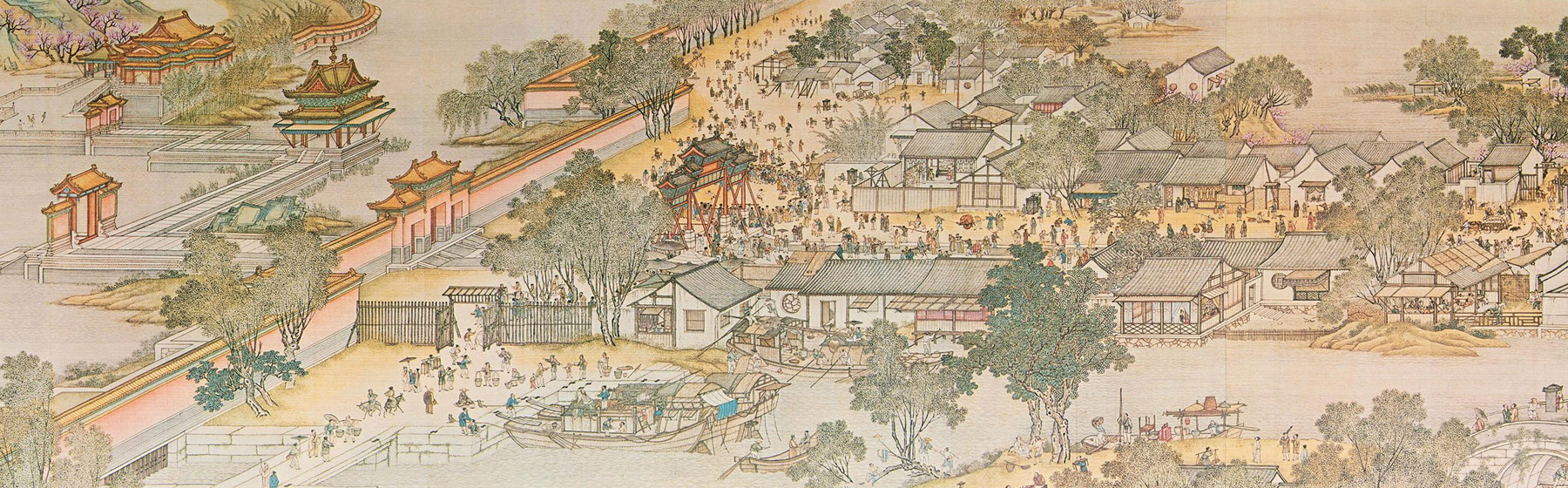

A very famous example of transmission-by-copying, one of Xie He’s Six Canons of Painting, is the Qing Dynasty version of Along the River During the Qingming Festival, completed by Zhang Zeduan in 1736 [1]. He was a pioneer in the grand scheme of Chinese landscape art, most famous for this particular handscroll. Many replicas of the original Song Dynasty rendition of the painting were created in later dynasties. The original scroll contained depictions of Song Dynasty lifestyle, including economic activities, clothing, and architecture [2]. The location shown was the Song Dynasty capital, Bianjing, which is now known as Kaifeng, lying in the Henan province. A subject of importance in Zhang Zeduan’s scroll was the economic growth and prosperity in China during the Qing Dynasty, as highlighted by the presence of stationary marketplaces. The Qing Dynasty marked the first time in Chinese history where stationary markets were established [3]. Such marketplaces were centralized locations that played into the idea that people could improve their welfare by trading [4]. For example, a person who farmed rice may have had a surplus of rice, whereas a person who produced tea may have had a surplus of tea, causing a trade to benefit both parties.

The Qing Dynasty was founded in 1644 after Beijing, China’s capital under the Ming Dynasty, was captured by the Manchus. During the Qing Dynasty, ports were opened to the western world, and literature began to be translated into Chinese, causing societal cries for the westernization and modernization of China, which met significant backlash from conservative officials. Despite this backlash, Chinese products began to be moved across great distances [5].

The replica of the famous Along the River During the Qingming Festival scroll depicts the economic prosperity from the time period. Towards the middle of the scroll, a town square of sorts can be seen, likely involving a marketplace. A river runs throughout the entire scroll, appearing to lead to the marketplace. The river holds many ornate ships; one of which, particularly large in size, appears to be passing beneath the Rainbow Bridge and heading towards the marketplace, with some form of cargo aboard [1]. This ship, along with its similarly elegant counterparts, represent the economic growth of China during the Qing Dynasty, which was spurred by trade with the western world, along with other parts of Asia. The Qing economy stood apart from the economies of the small European states at the time, since its reach knew no borders [6]. While the centralized marketplace at the center of the scroll served as a location for imports to be introduced and sold, it also allowed local merchants to reap the benefits of selling their own products.

Farming still comprised the bulk of the Qing economy despite the emergence of stationary marketplaces, because roughly 80 percent of the population at the time lived in rural areas [3]. Farms themselves are represented in this scroll; tilled fields and barns can be seen in great detail, thanks to the elegant brushstrokes and vibrant colors used by Zeduan. More importantly, this scroll shows the entire product flow of the era, with farmers growing and selling crops to both local and foreign markets. The farmers can be seen heading towards the marketplace with their products, and people can be seen leaving the marketplace with seemingly heavy parcels [1].

Overall, this was a significant change from the original scroll, completed during the Song Dynasty, as few such stationary marketplaces existed at that time, and it demonstrated China’s significant economic growth over that span, in spite of the ever-present shady political activity that was occurring.

Bibliography

1. “Whole Scroll · Qingming Shanghe Tu 清明上河圖.” n.d.

Digitalcollections.union.edu. Accessed November 12, 2021.

https://academic.schafferlibrarycollections.org/qingming-shanghe-tu/items/show/40#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=19762%2C33%2C2166%2C837.

2. “The Song Dynasty in China | Asia for Educators.” n.d. Afe.easia.columbia.edu.

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/songdynasty-module/intro-two-versions.html.

3. Zenith, Madeleine. 2005. Review of The Grandeur of the Qing Economy.

Afe.easia.columbia.edu. Columbia University. 2005. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/qing/downloads/economy.pdf.

4. “The Marketing System in Pre-Modern China.” n.d. Obo. Accessed November

12, 2021. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199920082/obo-9780199920082-0059.xml.

5. The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. 2018. “Qing Dynasty | Definition, History,

& Achievements.” In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Qing-dynasty.

6. “Grandeur of the Qing Economy.” n.d. Projects.mcah.columbia.edu.

https://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/nanxuntu/html/economy/.