Ryan Gallary - Gardens and Social Status

Gardens and Social Status

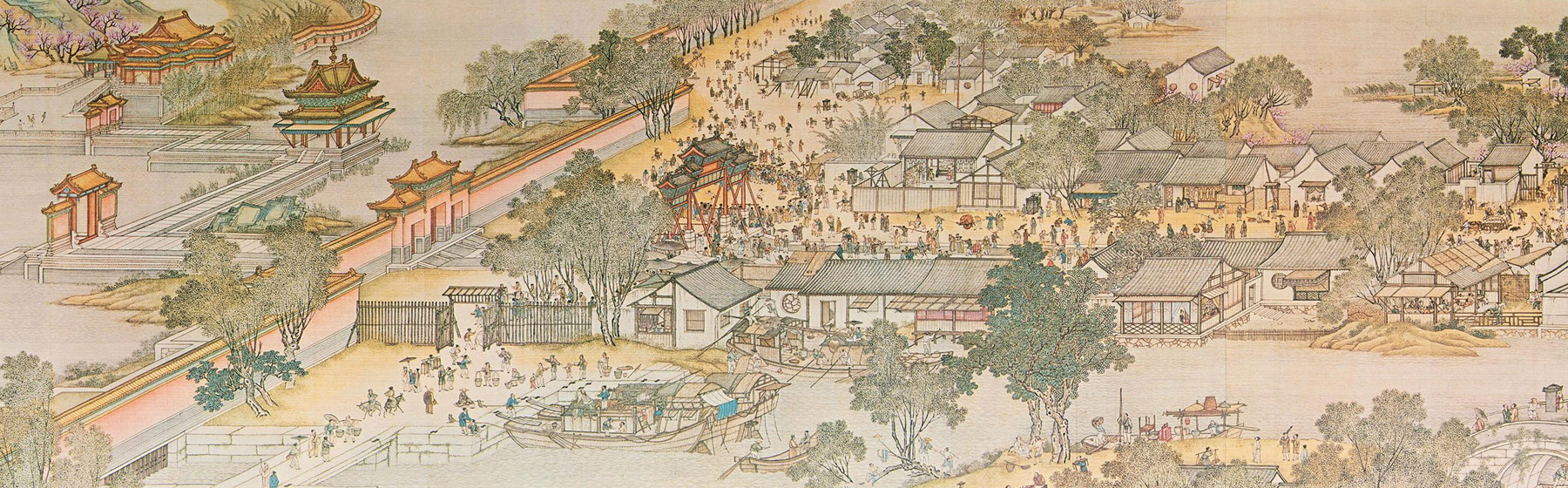

An extremely large number of gardens were built during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.) thanks to an increase in capital surplus from trade and subsequent changes in the rigid Confucian hierarchical system (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 1). This trade can be seen all throughout the Qing dynasty court version of the Qingming Shanghe tu. Cargo boats fill the water facilitating trade. In addition, individuals carrying litters and horse drawn carriages are seen in the streets. It cannot be seen if goods are inside, but it is likely that these are assisting with trade as well. Garden ownership, once an elusive privilege for wealthy elites, was now welcomed to the new class of more wealthy merchants that emerged (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 3). These merchants helped the art market flourish as a whole. Garden culture continued to spread further into the public realm during the early Qing (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 10). This spread created more diversity in garden landscapes over time, leading to the present day where virtually anyone can own and design their own garden. Although this seems like a very common privilege today, it is important to note that this was not always the case.

Three highly regarded garden design and theory books were published during the late Ming to early Qing Dynasty periods (16th-18th centuries). Zhangwuzhi (Treatise on Superfluous Things) by Wen Zhenheng, Yuanye (The Craft Of Garden) by Ji Cheng, and Xianqingouji (Casual Expressions) by Li Yu. The three authors belonged to different social classes with their works providing evidence of garden design ideologies important to their respective groups at the time. Wen Zhenheng was from a scholar-gentry family while Ji Cheng was a rather popular garden craftsman from the commoner class. Both of their publishings focused mainly on the importance of elegance in garden design. There were still large differences in their ideals though, as Wen Zhenheng adhered to elegance as a defining facet of elite gardens (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 4), while Ji Cheng believed that elegance should be used regardless of the customer's social status. In other words, he thought elegance was important in designing the ideal garden regardless of social standing (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 6). Li Yu, being from the lower middle class, builds further upon Ji Cheng’s ideals and stresses cheap and easily attainable materials that can produce elegance (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 8). Something originally only available for wealthy elites, was now more attainable to commoners with his ideals. These works show a common ideal of elegance in garden design for Chinese culture during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, but also how much garden design differed among social classes.

Evidence of some of the specific design elements mentioned in these works can be found in different social class gardens throughout the scroll. For example, Wen Zhenheng points out four landscape characteristics typical of literati gardens: rock piles, artificial water features, trees and plants, and architecture. It is said that, “Elegant trees symbolise the literati’s moral values, and the plain house style reflects the literati’s focus on the simple life” (Yun and Kim, 2018, p. 6). The gardens in the Imperial area of the scroll contain most of these elements with extremely elegant architecture and trees. On top of this, we see amazing rock structures, some so large they are mountain-like. The entire palace seems to be set within a vast garden with viewing pavilions seen throughout. In Chinese culture these rocks are meant to remind the viewer of the expressiveness of nature (Murck and Fong, 2012, p. 52). Taihu rock peaks specifically were sought after for their amazing appearance and they can be seen all throughout the Imperial gardens in the scroll. By the late Ming period though, there was even a shortage in good peaks because of their popularity (Murck and Fong, 2012, p. 53). Many similar features are seen in the gardens of the city area of the scroll, but on a slightly smaller scale. This makes sense due to the limited supply of some of the more spectacular features. Elegance is very prominent in these gardens as well, possibly due to their close proximity to the imperial palace. Moving to the lower class areas of the scroll, we see evidence of the design principles mentioned by Li Yu. These include simple architectural methods and utilization of inexpensive materials. On the scroll this includes enclosed spaces and pavilions like the one seen on the hill in section 3. We can not be certain what materials are depicted, but certainly simpler architecture is seen.

Bibliography

Yun, Kim. (2018). “Sociocultural factors of the late Ming and early Qing Chinese garden landscape, based on philosophies seen in Yuanye, Zhangwuzhi, and Xianqingouji.” Landscape Research. 44.

Murck, Alfreda, and Wen Fong. (2012) “A Chinese Garden Court: The Astor Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Metropolitan Museum of Art.