Methods and Institutions

Ostforschung as a field of historic research was innovative. Traditional history writing in Germany would still follow the traditions of historism. These would focus on political categories like statehood or nation. In contrast, Ostforschung chose the land itself as the major concern of its analyses, predating the 'spatial turn'.

Studying diplomacy and warfare still played an important role, but so did geography and various forms of economic or population statistics. They were considered important ingredients to answer the underlying question: How did the landscape -- understood in a very wide sense --, its culture and the people living there shape each other? Acknowledging these reciprocities in the first place meant an important paradigm shift.

While this fundamental question was honest, the more specific notions German scholars set out to inquire and the answers they obtained were not. Their research served the purpose of proving culturally diverse lands German, while disproving corresponding claims by Polish scholars. Often they simply rejected the latter as “unscientific”.

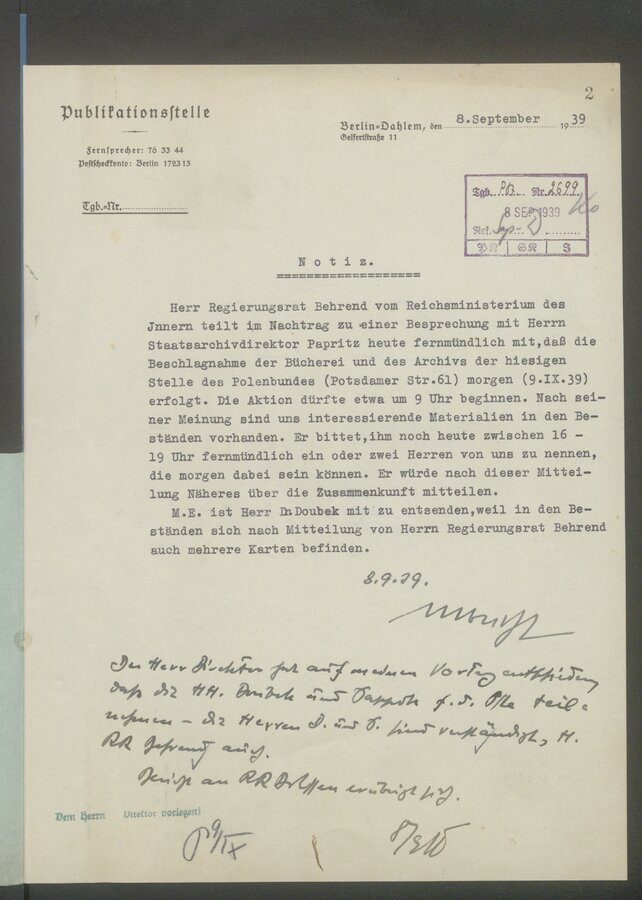

Guaranteeing both politically favourable and influential results required a good deal of organisation. This was achieved by the Nord- und Ostdeutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (NOFG, "North and East German Research Community") and its associated Publikationsstelle Berlin-Dahlem (PuSte, "Publication Office").

The main building of the Prussian Privy State Archives in Berlin. The Publication Office Dahlem (PuSte) was founded in 1931 as a subdivision, but as its tasks grew more diverse, it moved to a seperate, less representative site in 1938.

Prussian Privy State Archives

PuSte and NOFG

Under the supervision of Albert Brackmann, the Publication Office and the NOFG, founded in late 1933, became the symbiotic backbone of German Ostforschung. While the NOFG was structured as a research community that coordinated local institutes, sponsored conferences, edited publications and whose board decided on grants, the PuSte held more practical responsibilities. However, this distinction would only stand for accounting purposes as the staff was largely identical and the PuSte had its own grants and publications, too.

Ostforschung was thus largely independent of the German university system and had rather strong ties with the archival administration and the Ministry of the Interior that provided generous funding. Notable local institutions to profit from this system include the Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit Cracow (IDO, "Institute for German Eastern Activity"), Osteuropa-Institut Wroclaw (OEI, "Eastern Europe Institute") and Ostland-Institut Danzig/Gdansk ("Eastlands Institute"). Together, PuSte and NOFG would support, administer and oversee all other efforts in Ostforschung in manifold ways:

Collections and Translations

Although it slowly loosened its ties to the Prussian Archives, the PuSte would always remain faithful to its origin as a scientific archive. During the Nazi reign, it continuously expanded its library and collections of periodicals, maps and other print materials on and from Eastern Middle Europe. Profiting heavily from raids and looting in archives of the occupied countries, the office managed to gather an unparalleled research library with the Bibliothèque Polonaise in Paris as its most important wartime "addition".

While Brackmann’s stated purpose to oppose, refute and debunk Polish “research propaganda” was commonly approved, most scholars lacked the language knowledge to engage with the outcomes of Polish Western Research. The PuSte took over a service that had previously been offered by the Danzig Ostland Institute: Translations of Polish news and research papers for internal use. The Ostland Institute was founded as a subdivision of the Danzig City Archives in 1927. It focused on publications of the Polish Instytut Bałtycki that it summarised and commented in harsh, often anti-slavic terms. The PuSte would include a wider range of publishers, languages (Scandinavian, Baltic and East Slavic) genres (like a theatre play on the Reichstag fire) and recipients in academia, military and government. During war time, the focus shifted to issues of exile newspapers.

Publishing and Conferring

In its translations, the PuSte refrained from further commenting the works, although the choice of translations and omissions naturally implied some preconceptions. Ideological statements are found more explicitely in its publications aimed at the general public or an international research community. The most important outlet that still claimed scientific standards was Jomsburg, published from 1937 to 1942/4 in response to the Polish English language journal Baltic Countries, later renamed to Baltic and Scandinavian Countries. Soon forbidden in Poland, it provided a mixture of anti-Polish rhetoric by NOFG associates and genuine research work on Scandinavian and Eastern European history, though subordinated to political demands. It was complemented by a series of monographs on “Germany and the East”.

Moreover, the PuSte supported Ostforschung’s public outreach. For this purpose it contributed to various print projects in and outside Germany. For instance, it subsidised a small series of regional historical booklets by ethnic Germans in Poland that emphasised German contributions to the local cultural identity.

A planned series of tour guides (“Seen through our eyes: German Cities in the East”) was started with a first volume on the recently occupied Cracow in 1940. A second volume on Upper Silesia’s industrial cities that had already been printed burnt in an air raid. Plans to recompile the book as well as a third volume were made, but never put into action. This seems to be a common fate for PuSte publications, befalling the Jomsburg’s 1943 edition among others, too.

Maps

The PuSte also produced large amounts of maps, covering administrative borders or census data across Eastern Europe. These detailed visualisations of political, religious or economic connections were sold not only to academic institutions, but also to a plethora of military and civil administration offices. Their use in ethnic cleansing has been suggested, but could so far not be fully established.

Grants

In assigning grants and other funding opportunities, PuSte and NOFG made sure that the research output was deemed politically favourable. In a 1944 report, the PuSte boosts that „publications that could have politically harmed the German cause, were mostly avoided at the outset. Only in rare occasions, a proscription had to precipitated.

Often grants concerned dissertation projects or short research stays. Sometimes, the money was simply passed based on personal need: When the Polish Government closed down schools of the German minority in 1937, Albert Breyer, a teacher and regional historian of the Posen /Poznan region, obtained a stipend with flimsy academic strings attached to help his family in this situation. He had previously written a booklet on this region’s history for a PuSte supported German society in Posen and kept close ties to some PuSte employees. After the German invasion, he was conscripted by the Polish army and died in the first days of the war. After German occupation, the PuSte helped his widow to receive the pension of a German teacher.

Further Reading

Michael Burleigh: Germany turns eastwards. A study of Ostforschung in the Third Reich. Cambridge University Press 1988.

Martin Munke: Publikationsstelle Ost. In: Online-Lexikon zur Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa, 2013. URL: ome-lexikon.uni-oldenburg.de/62681.html (15.11.2021)

Martin Munke: Publikationsstelle Berlin-Dahlem. In: Online-Lexikon zur Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa, 2013. URL: ome-lexikon.uni-oldenburg.de/53902.html (21.06.2021)