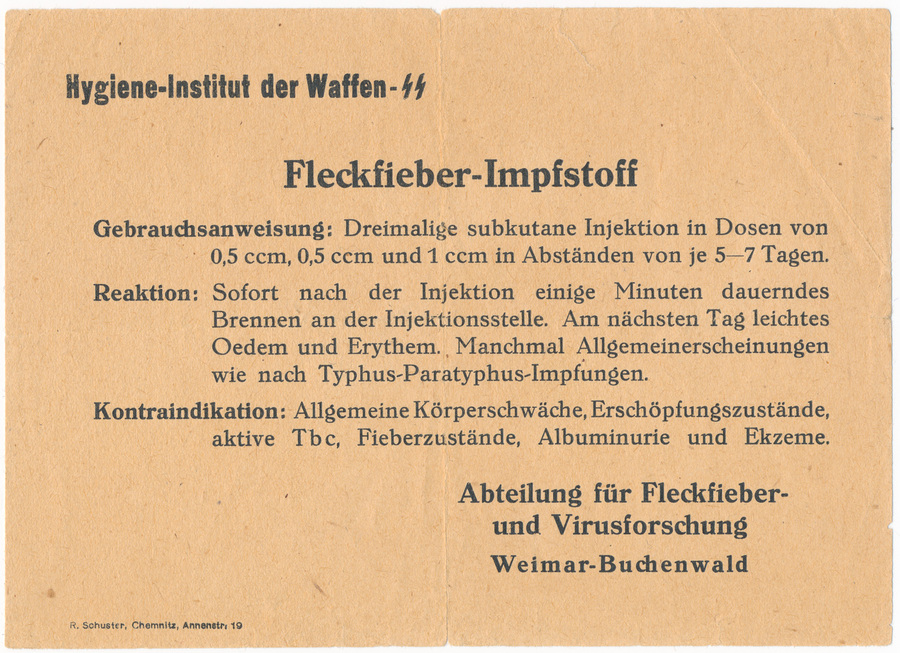

Hygiene Institute of the Waffen SS

The Berlin Hygiene Institute of the Waffen-SS (HI-WSS), was the SS’s central institution for hygiene and disease prevention. Its main responsibilities were public health of SS troopers and police within and outside of concentration camps. Under the pretext of fighting epidemics, it conducted numerous experiments on concentration camp prisoners with pathogens or poisoned ammunition, and was responsible for the supply chain and deployment of the infamous Zyklon-B. The head of the institute, university lecturer and “chief hygienist” Dr. Joachim Mrugowsky, was sentenced to death and executed at the Nuremberg doctors’ trial.

Dates and places

The institute, already under construction in 1937, was officially founded in 1939 as “Hygienisch-bakteriologische Untersuchungsstelle der Waffen-SS” (hygienic-bacteriological investigative unit of the Waffen-SS), and renamed Hygiene Institute of the Waffen-SS in 1940. Its Berlin head offices were located in Knesebackstrasse 43-4, in Charlottenburg, at least until May 1943, before moving to Spanische Allee 10-12, in Zehlendorf. Two construction plans in the Berlin districts Wilmersdorf and Prenzlauer Berg are preserved in the German Federal Archive, but were possibly abandoned before they started because of the course of the war. By 1942 the institute had opened and was running various research facilities outside of Berlin – such as the department of blood conservation in Frankfurt am Main – several of which based inside or near concentration camps, like the institute for virology and typhus in Buchenwald, and the hygiene institute for serological testing in Auschwitz (later relocated to Rajsko). They also supplied three field labs and forty SS doctors for research in the occupied lands in the East, got control of several scientific and hygienic institutions in Ukraine and supported an Institute for Medical Entomology in Riga in collaboration with the Ahnenerbe.

Areas of activity, responsibilities, tasks, goals

The HI-WSS’s main official responsibilities were the public health and hygiene of SS members, other military forces and police, including the ones working inside concentration camps. From a perspective that fused medicine with ideas of race and heredity as well as with nationalism, this came to include racial-based recruiting as well as monitoring of political attitude, ancestry, “intelligence”, etc. The specific target of the institute may help explain its existence, considering that Berlin already had at least two other institutions – the Hygiene Institute of the Kaiser Wilhelm University founded in 1885 and run by Heinz Zeiss since 1933, and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, founded in 1927 and directed during the Nazi years first by Eugen Fischer and then by Otto von Verschuer – that covered similar areas of research and activity.

The HI-WSS’s was by the way also part of a broader SS agenda aimed at expanding its influence on military and civilian medicine, creating strong links between military strategy and the medical sphere, and, ultimately, gain more power.

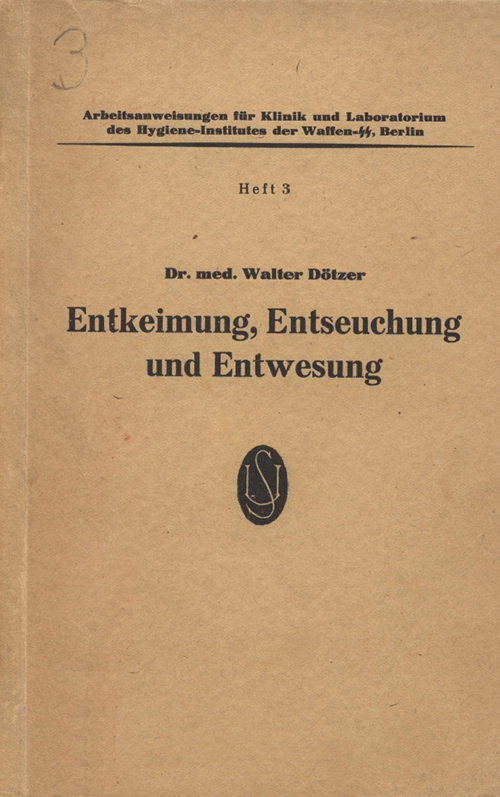

In the years of its activity, the HI-WSS built a staff of about 200 people organized in several departments, with expertise and ability to provide services in fields as diverse as bacteriology and serology, sanitation and disinfestation, disease and epidemic control, nutrition and food surrogates, pest control, medical zoology, geology and hydrology, hereditary and constitution medicine, occupational health and safety.

The most infamous and well-researched projects undertaken by the HI-WSS are the experiments on human prisoners in concentration camps – including tests with vaccines, medicines, pathogenic agents, poisoned ammunition and dubious food surrogates – and the supply chain of Zyklon B. Zyklon B was first implemented as pest control measure, for example against bed bugs, to protect SS troupers and police, its deployment was strictly regulated and could be performed exclusively by trained SS personnel. The involvement of the HI-WSS in the deployment of Zyklon B for the mass-murder of concentration camps prisoners is a complex and not yet completely cleared topic.

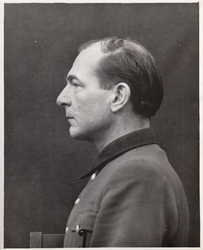

Joseph Mrugowsky: the head of the HI-WSS

The ambition and connections of Joseph Mrugowsky, the head of the HI-WSS, played a key role in the history of the institute and of hygiene in the Nazi regime at large. A typical example of Nazi medical activists of the younger generation, Mrugosky was born in 1905. His father, a physician, had died in WWI, and he had experienced hard times as a youth. After his medical studies in Halle (1925-31), he completed doctorates in botany (with Valentin Haecker same teacher as Darré and Himmler) and medicine. He joined the Nazi Party and SA in 1930, but transfered to SS already in 1931, because that seemed to offer better career prospect. He was first assistant at the Hygiene Institute Halle, with a focus on disinfection techniques, and later political security officer for the SS, before being appointed, in 1938, head of the still under construction HI-WSS directly by Heinrich Himmler.

Building on his interdisciplinary academic background, typical of hygienists at the time, Mrugowsky applied ecology and sociology of plant communities to racial hygiene, was a geo-medicin enthusiasts, promoted a „holistic“ vision of the medical science, and criticized Koch’s bacteriology as too narrow.

Mrugowsky was very ambitious, and built useful and long-term connections that helped him and the HI-WSS gain more and more power: he was an ally of Zeiss, who secured him a Privatdozent title in 1939, collaborated with the KWI-A and the Ahnenerbe in several occasions and contexts, and engaged in power struggles with prominent colleagues such as Carl Genzken and Ernst-Robert Grawitz.After the war, he was one of the few Nazi doctors called upon to explain and justify their unjustifiable conduct and practices during the so-called “doctors’ trial” in Nuremberg. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1948.

Literature

EN

Robert J. Lifton (1986): The Nazi Doctors. Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books.

Paul Julian Weindling (2000): Epidemics and Genocide in Eastern Europe, 1890–1945. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

DE

Florian Bruns: Medizinethik im Nationalsozialismus. Entwicklungen und Protagonisten in Berlin (1939–1945). Geschichte und Philosophie der Medizin 7. Stuttgart 2009.

Hahn, Judith u. Ulrike Gaida, Marion Hulverscheidt (2010): 125 Jahre Hygiene-Institute an Berliner Universitäten. Eine Festschrift. Berlin: Institut für Hygiene und Umweltmedizin, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Flamm Heinz (2007): „Die Geschichte der Tropenmedizin und Medizinischen Parasitologie in Österreich. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 119 [Suppl 3]: 1–7.

Wachsmut, I. u. Sommer R. (2011): “Menschenversuche und Lagerhygiene. Die Arbeit des Hygiene-Instituts der Waffen-SS in den NS-Konzentrationslagern”. Gesundheitswesen, 73 - A53.

Kalthoff, Jürgen u. Martin Werner (1998): Die Händler des Zyklon B – Tesch & Stabenow Eine Firmengeschichte zwischen Hamburg und Auschwitz. Hamburg: VSA Verlag Hamburg.

Scharsach, Hans-Henning (2000): Die Ärzte der Nazis. Wien, München, Zürich: Orac.