Case study: Siemens in Ravensbrück

In retrospect, one may wonder how it could happen that within a few years production took place under such inhumane conditions. Of course, no all-encompassing answer can be given. Certainly, it speaks for the fact that the majority of the German population was racist and anti-Semitic. But this alone cannot explain why companies used the plight of imprisoned forced labourers for their own purposes. This exhibition now attempts to substantiate an answer to this question. It is: Rationality of purpose.

Siemens

The electrical industry in Germany was an important part of the German arms economy. After the start of the war, even the production of light bulbs was important for the defence economy. Thus, the light bulb produced by the Siemens subsidiary Osram became a technology needed for the war. But not only Osram, but also Siemens itself was part of the German armaments industry.

Today, Siemens is known for automation, digitalisation, infrastructure energy systems, mobility, medical technology and much more. Siemens, as we know it today, was formed by the merger of the predecessor companies Siemens & Halske AG, Siemens-Schuckertwerke AG and Siemens-Reiniger-Werke AG. Other predecessors, such as Osram or Siemens-Bauunion, are no longer part of the group. All of these predecessor companies used forced labourers during the Nazi regime. This exhibition aims to show how this happened.

The use of forced labour took place in two phases: In the first phase from 1939 to 1942, the forced labourers still worked on site in the production facilities. In the second phase from 1943 until a few days before the end of the war in 1945, work was decentralised. The Ravensbrück women's concentration camp will be shown as an example of this phase.

Before the war

At the beginning of the war in 1939, the German electrical industry was well prepared for war. Siemens in particular was able to make large profits at the beginning of the open rearmament in 1933/34. One reason for this was that Siemens had moved its electrical division to other European countries. This made it possible to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles, which prohibited or severely restricted rearmament. Siemens also gained experience with its factories in China. There, production was carried out with up to 80% foreign workers within the workforce. When the Four-Year Plan, which was supposed to prepare the German economy for war, was announced, Siemens was accordingly well prepared. The experience of decentralised work, or 'verlängerte Werkbank' (extended workbench), gained by Siemens here was to be of use later.

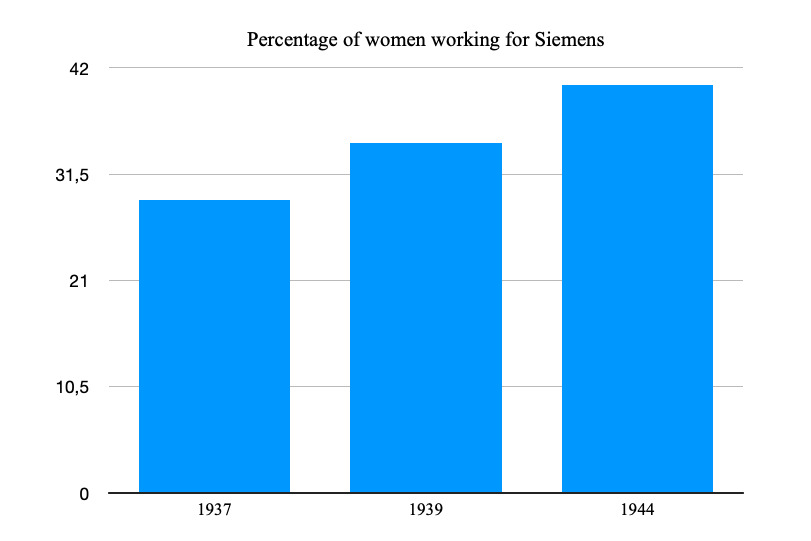

When employment at Siemens reached the 1928 level in 1937, 28.9 % of the workforce were women. This figure rose to 34.6 % in 1939 and reached 40.3 % in 1944. This was typical for a corporation in the electrical industry. There was a stereotype that women were better suited than men for monotonous work like winding wires. Moreover, women could be paid lower wages.

As the war progressed, more and more foreign workers were employed. In 1944, they made up one-fifth of the workforce. Half of them were women. This means that Siemens employed on average as many women as other companies in the electrical industry, but significantly more foreigners than the average.

1st Phase 1939 - 1942: Local forced labour

Significantly, the use of foreign labour began with the re-employment of Germans of the Jewish faith who had been dubbed 'Jews'. After they had been expelled from the factories, they were reassigned to them from 1940 onwards. It could not be justified to leave the Jews without employment, according to a report by the social policy department of Siemens. The fact that there was already a shortage of skilled workers, which they tried to compensate for with Jewish workers, was not mentioned.

Special regulations were made for the employment of Jewish workers. They were not paid on holidays or in the event of air raid alerts. In addition, they were kept in and out of the factories and were not allowed to work in the same room as German workers. Siemens employed a total of 500 conscripted Jewish workers as early as 1940. Even though the initiative for this did not come from Siemens, the company management considered the results to be positive. Siemens' first experience with foreign workers during the Second World War was thus not with people from abroad, but with Germans who were no longer considered German.

Motivation through indirect death threats

The positive assessment of the use of conscripted Jews may have been due above all to the fact that factory engineers and foremen quickly discovered that the threat of dismissal spurred the workers on to top performance. This was because since the deportations of Berlin Jews had begun in autumn 1941, a dismissal meant deportation, which was often tantamount to death.

These deportations were booked by the social policy department at Siemens under 'evacuation measures'. The increasing deportation of Jews to concentration and extermination camps reduced the number of Jewish employees at Siemens. In 1943, the statistics ended

.

Between 1942 and 1943, the use of foreign workers was in transition. Both workers with temporary contracts (e.g. French, Danes and Italians) and 'indefinitely assigned' 'Ostarbeiter' (Eastern workers) worked for Siemens. To ensure that the company could continue to run smoothly despite the ongoing deportation of Jewish workers, the Jewish workers were ordered to train other foreign workers. Workers could therefore be replaced without major problems.

For other unfree workers, too, the cost-benefit calculations remained controllable through sanctions such as 'performance withholdings'. Siemens combined this with bonus payments so as not to jeopardise the 'piecework adjustment'. Chief engineer Mohr from Siemens was pleased that seldom had the form of performance monitoring taken such a hit as this one. Also, permanent cards were introduced for foreign workers, on which absenteeism and sick days were recorded.

All in all, Siemens took great pains to keep costs low. To this end, the workers were to achieve high performance as quickly as possible. To achieve this, the most capable workers were selected in a 'quality selection' and then trained. The costs for administration, air-raid protection, 'disinfestation', guarding, rent and wage costs were also to be saved. This proved difficult, as new barrack camps had to be built to accommodate the increasing number of foreign workers. In order to find a balance between effort and return, it should therefore be avoided that trained workers leave the employment relationship or that the will to work is reduced because of a 'bad camp'.

What such a working environment should look like according to the ideas of the Siemens management is illustrated in the following section using the women's concentration camp Ravensbrück as an example. It should not be forgotten that Siemens also had production in other concentration camps.

2nd Phase 1942 - 1945: Decentralised forced labour

Since the deportations, Siemens could foresee that the use of forced labour by Berlin Jews would not last. Therefore, preparations for production in concentration camps soon began. As early as December 1942, Siemens negotiated the construction of the 'Ravensbrück production plant' during an internal meeting.

Since in the course of that year the pressure to rationalise the use of manpower had increased even more, they now discussed how production could be made even more effective despite the shortage of manpower and the high production costs. It was decided to minimise waste and disruption in the use of human labour. Forced labourers were now seen exclusively as a (disruptive) factor in production. This dehumanisation was an important step on the way to moving production facilities to a concentration camp.

Nevertheless, the work in the Siemens camp was perceived as better compared to the harassment and more likely death in the main concentration camp. With this sword of Damocles hanging over their heads, the women worked day and night in nine-hour and later eleven-hour shifts. This sense of threat was factored into the piecework rates and exploited by Siemens to achieve maximum output. If a woman became ill or did not meet the standard, she was sent back to the camp and was replaced. This was not the will of the guards or the SS, but had been decided by Siemens at a meeting on the use of foreigners.

In order to statistically monitor the hourly performance of the prisoners, Siemens needed bureaucratic controls, as in the main factory. In Ravensbrück, prisoners drew up performance charts on graph paper for this purpose, which were used to decide on the welfare of the women. In particular, it depended on whether the prisoners' wives were punished or rewarded with special payments as an incentive to increase production. In the last few years, however, nothing but salt and fish paste could be bought with these special payments. Department heads and foremen were always amazed at the production output that could be obtained from the exhausted prisoners' wives. The performance bonus was a tried and tested means of increasing this even more. Another possibility was to shorten the journey by building a dormitory next to the production site. In this way, the degree of utilisation of the prisoners could be increased even further.

Good connections in politics

A further indication of the active efforts to make production possible in Ravensbrück can be found in the proximity to the office of the 'Beauftragten für die Verlagerung der Elektroindustrie' (Commissioner for the Relocation of the Electrical Industry), founded in 1943 and headed by Siemens director Friedrich Lüschen. Lüschen was also Speer's armaments minister's right-hand man in all matters of electrical engineering for the armaments industry. Siemens thus used both the 'extended workbench' experience gained in previous years and its connections in the Nazi leadership to push decentralisation and production in concentration camps.

After calculations were made to reduce the increased costs of using foreigners, Siemens concluded that foreign labour could only replace a German worker at 120% output. The solution to this was that large-scale adjustments had to be made to get by with only a few German workers and many foreign workers. This was based on the experience Siemens had already gained with its factories in China before the war. There Siemens produced with a proportion of up to 80% foreign workers within the workforce. In addition, the surveillance and punishment system was to be further expanded and camps converted into an inescapable enclosure system. Siemens had now adjusted to the work of forced labourers.

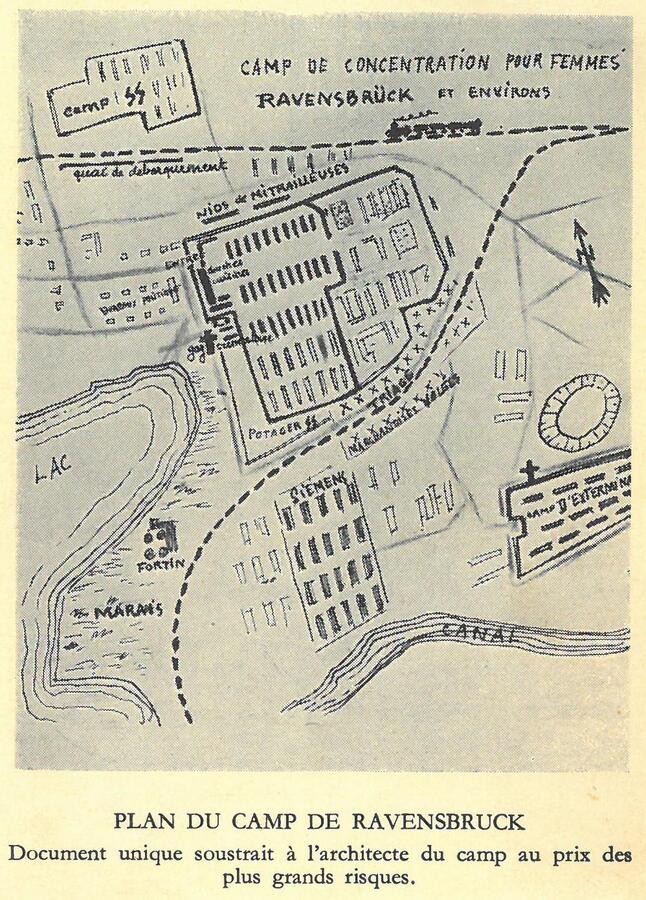

As a result, construction of the so-called Siemens camp began on 8 June 1942, right next to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. As early as September 1942, the first 300 female prisoners were employed. By the time of liberation, the Siemens camp had grown to a size of 20 barracks and an area of 675m^2 in which 2,307 prisoners were forced to work in January 1945. After production began for Siemens in September 1942, electronic components such as relays, microphones and switches were manufactured.

The workplaces in the Siemens camp were heated, had large windows and work was allowed to be done sitting down. However, these 'amenities' were hardly for the well-being of the workers, but rather to increase their performance. One reason for this is that these 'amenities' did not extend to the living quarters for the prisoners, which were built later. This was unheated and the prisoners had to defecate in full view of the guards. Secondly, it would simply not have been possible to bend the filigree wires in the cold - especially not with stiff fingers.

Which of the prisoners were sent from Ravensbrück concentration camp to the Siemens camp was by no means left to chance or to the SS. Siemens representatives selected the women according to their manual and craft skills. For this purpose, the women were examined like "merchandise", recorded in a list, asked about their previous jobs and forced to bend figures out of wire as an aptitude test.

Until the liberation of the concentration camp, at least 2100 children and women worked for Siemens in Ravensbrück.

Literature:

Fröbe, R. (1991). Der Arbeitseinsatz von KZ-Häftlingen und die Perspektive der Industrie, 1943–1945. In U. Herbert (Hrsg.), Europa und der Reichseinsatz: Ausländische Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangene und KZ-Häftkinge in Deutschland 1938–1945 (1. Aufl., S. 351–383). Klartext-Verlagsges.

Jacobeit, S. (1999). Arbeit für Siemens in Ravensbrück. In D. Eichholtz (Hrsg.), Krieg und Wirtschaft: Studien zur deutschen Wirtschaftsgeschichte (S. 157–169). Metropol.

Roth, K. H. (1996). Zwangsarbeit im Siemens-Konzern (1938 - 1945): Fakten – Kontroversen – Probleme. In H. Kaienburg (Hrsg.), Konzentrationslager und deutsche Wirtschaft 1939–1945 (S. 149–169). Leske + Budrich.

Sachse, C. (1991). Zwangsarbeit jüdischer und nichtjüdischer Frauen und Männer bei der Firma Siemens 1940 bis 1945. Internationale wissenschaftliche Korrespondenz zur Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, 1(91), 1–12.

Scherner, J. & Streb, J. (2010). Ursachen des „Rüstungswunders“ in der Luftrüstungs-, Pulver- und Munitionsindustrie während des Zweiten Weltkriegs*. In A. Heusler, M. Spoerer & H. Trischler (Hrsg.), Rüstung, Kriegswirtschaft und Zwangsarbeit im „Dritten Reich“ (S. 37–60). Oldenbourg Verlag.

Schmolling, R. (2009). Ravensbrück Subcamp System. In G. P. Megargee (Hrsg.), The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Volume I (S. 1192–1228). Indiana University Press.

Siegel, T. & Freyberg, T. V. (1990). Industrielle Rationalisierung unter dem Nationalsozialismus (Forschungsberichte aus dem IfS Frankfurt) (1. Aufl.). Campus Verlag.

Go back and read about the contexts and backgrounds of forced labour.

Take me back to the introduction.