Max Levenson - Chinese Junks and Maritime Trade

Chinese Junks and Maritime Trade

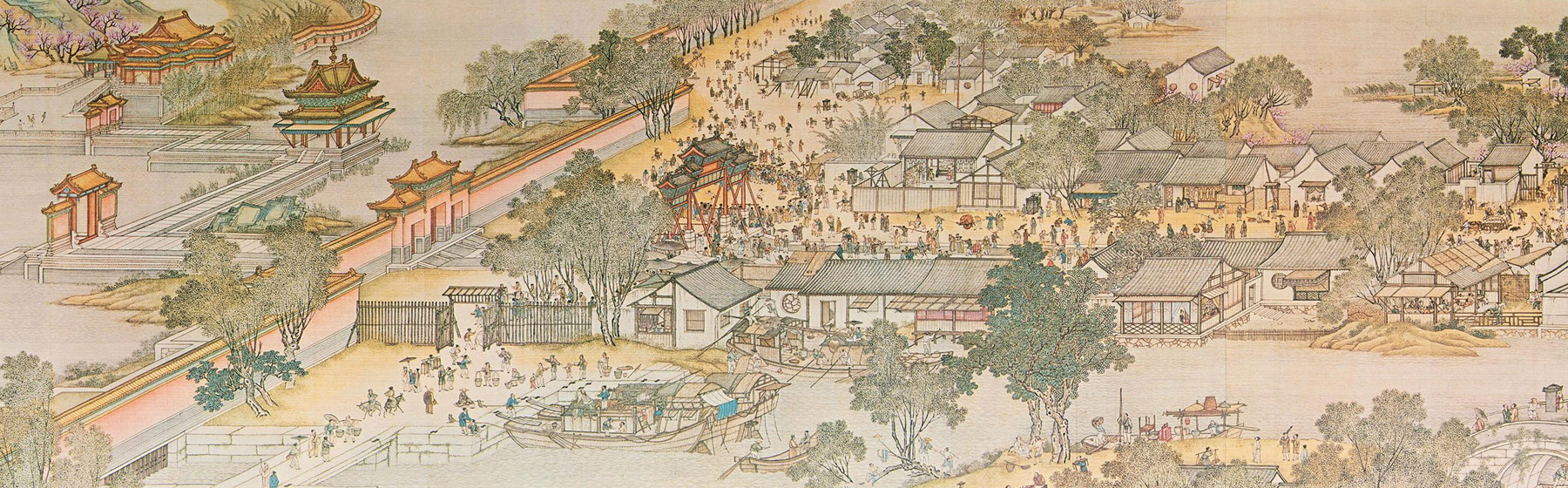

While browsing through the Qingming Shanghe tu Scroll, it was the role of the boats that caught my attention as they are placed throughout the waterway in the scroll. Seafaring has been an important part of the Chinese economy for as long as the Middle Kingdom itself. Coastal cities facilitated regional trade within the empire, and became more important as foreign powers made their way into China starting before the thirteenth century. The Yangtze, a culturally significant river the length of one fifth of the country, also has a rich cultural history and has served as a major maritime trade inlet. The Chinese most commonly used small sailing boats known as Junks in maritime travel and commerce. Junks were a staple of maritime life in central and southern China. These boats were also employed by the imperial government in numerous wars throughout multiple dynasties. These boats were an integral part of Chinese maritime culture, as well as important in defining the early international trade networks of China and Southeast Asia.

In Southern China, maritime trade was immensely popular because of the rough, mountainous terrain that made traditional on-foot travel tedious and inefficient. Many other rivers in China along with the Yangtze were utilized by countless merchants for domestic trade and travel. Travel and trade in Northern and Western China had been defined by on-foot travel through the Silk Road, a millenia old trade network connecting China and Europe. In Southern China, the waterways were their own domain to be conquered. The superiority and popularity of waterway maritime travel has led historians to consider the existence of a “water frontier” within China. This argument is supported by the mysteriousness and folklore surrounding the West in Chinese theology. The majority of these waterways originate from the ocean and gradually make their way westward within China, Vietnam and Thailand. Yet, this form of trade and transportation was limited by the seasonal monsoons, which frequently changed the direction of the flow of waterways, as well as the flow of water up and down the coast of China (Lockard, 2010, pg. 220).

By the middle of the 19th century, Junk boats numbered around twenty thousand. Junks out of Shanghai had been engaged in northern trade routes, along with original responsibilites to trade within the Yangtze (Wiens, 1955, p. 248). Despite being generally smaller vessels compared to grander warships and exploratory vessels also found in imperial China, Junks were able to survive travel up and down the coast of China by utilizing seasonal currents to manage a full year trade cycle. Rice and other grain were among the most prominent goods exchanged within the empire (Wiens, 1955, p. 249). The most Junks could be found, starting in Shanghai, along the Yangtze River. Even after the introduction of steamships in the late 19th century, the Junks were still commonplace as merchants had found success in the millenia-old boat design. The Junks, along with the cargo, typically carried a crew of 8, all of whom worked for the owner of the junk, or more commonly, the rich merchant owner of a fleet of junks (Wiens, 1955, p. 253). As imperial China progressed through the centuries, more trade networks were established internationally.

Junks were significant in the relationship between China and the Sultanate of Malacca in the early 1500s. A handful of Malaccan junks would enter Chinese ports annually bringing highly sought after foreign goods. The Sultanate even found it necessary to conscript Chinese junks for use in Malaccan war matters (Lockard, 2010, p. 231). Domestically, junks found more importance and use among Chinese commonfolk peaking in the 18th century. Junks had become utilized by merchants, craftsmen, innkeepers, grocers, and other important figures in Chinese daily life (Lockard, 2010, p. 236). Junks were also used in trade between Japan and China. The two empires, historically in stages of periodic conflict, found a massive mutual trade network starting in the thirteenth century. By the seventeen hundreds, thousands of ships were travelling between the coasts of China and Japan. (Lockard, 2010, p. 245).

Work Cited

Lockard, Craig A. “‘The Sea Common to All’: Maritime Frontiers, Port Cities, and Chinese

Traders in the Southeast Asian Age of Commerce, Ca. 1400–1750.” Journal of World

History 21, no. 2 (June 2010): 219–47.

Wiens, Herold J. “Riverine and Coastal Junks in China's Commerce.” Economic Geography 31,

- 3 (July 1955): 248–64.