Kendall Eaton - Man’s Best Friend: the Changing Roles of Dogs in Ancient China

Man’s Best Friend: The Changing Roles of Dogs in Ancient China

As early as nine thousand years ago dating back to Neolithic times, the domestication of dogs has been in practice in China. Being the oldest domesticated animal, dogs have remained significant throughout ancient Chinese history and continue to hold a large presence in the modern-day. From their ties to the Chinese calendar and astrology to their influence on the empirical level, these animals have shaped ancient Chinese society in profound ways.

The Chinese zodiac, also known as the Sheng Xiao or Shu Xiang, operates on a twelve-year cycle consisting of animal signs. According to legend, the mythical Jade Emperor asked twelve animals to help guard the entrance to heaven with the order of their arrival signaling each zodiac’s order on the calendar. The dog holds position eleven.

In Neolithic times, dogs were bred for protection, hunting, and as a source of food. Given the instability that came with such early societies, keeping dogs around ensured a level of security to the Neolithic people (Dai, 2018). In the Shang dynasty, the first signs of dogs used in burial appeared. Archeologists have found inscriptions on oracle bones containing references to sacrificial practices where dog sacrifices were used to ward off evil and appease the gods (Lu, 2018). During the Han dynasty, pottery figures depicting dogs and other animals were used in place of actual sacrifices to accompany the tomb occupant in the afterlife. Early Chinese nobles and elites would feast on dog meat as it was considered to be a delicacy for many years. Dog meat was thought to hold many medicinal benefits, including fatigue reduction. Following the dynasties of the first millennium, the spread of Buddhism across China led to widespread discontinuation of dog meat in popular society as Buddhism outlawed the consumption of certain animals, including dogs. Throughout the later dynasties of China, the primary purposes of dogs in society were guarding, herding, and hunting (Lu, 2018).

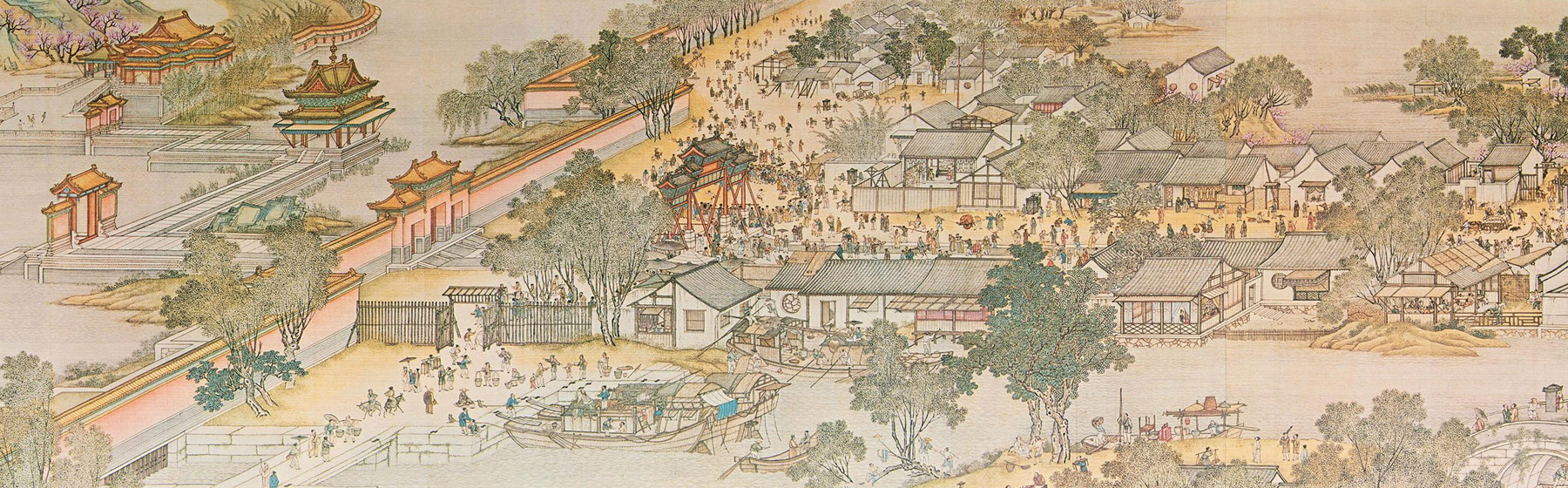

In the Ming and Qing dynasties, hunting was mainly done as a leisure activity by the nobles. Dogs, particularly the xigou breed, were used for their keen skills to hunt rabbits and similar small prey (Dai, 2018). Amongst the urban and rural citizens within the scroll, dogs similar to the xigou breed can be seen following behind hunters and commoners alike. Particularly in rural settings, dogs appear to be herding sheep alongside their owners. Along with dogs, the Qing dynasty palaces were known for their vast collections of pets, such as “birds, cats, crickets, and long-horned grasshoppers” (Wei, 2005). It was during this time that the Pekingese breed rose to prominence, especially in the royal court. The smaller dogs depicted throughout the scroll resemble the Pekingese and Maltese breeds. The toy breeds were especially popular among the ladies of the court, favored for their cute features and lap-dog attributes. Other popular breeds at the time include the greyhound, the snub-nosed mastiff, and hunting hounds (Schafer, 1963). While no imperial dogs can be viewed in the scroll, the court ladies depicted within the imperial space would likely have owned several. They lived in pavilions with luxurious marble floors, slept on cushions made of fine silk, and were walked, dressed up, and played with in great quantity. Fantastical dog cages were made and can be observed in modern museums today (Philadelphia Museum, 2021). Empress Cixi of the late Qing dynasty was particularly fond of dogs, owning dozens and gifting many to others throughout her reign. Among the common folk, dogs doubled as handy rat catchers and can be seen in various tomb paintings dating back to the Han-era (Dai, 2018).

With the rise of Buddhism in China also came a rise in the popularity of dogs. Lamaist Buddhism placed a large emphasis on the symbol of a lion to mean passion, and dogs with their lion-like features became associated as a result. The Buddha supposedly was able to tame the wild lion who trotted by his heels like a pet. Followers of Buddhism began to keep dogs as their pets to model after the Buddha himself (Tuan, 2016). This was especially true of the Pekingese breed with their round cheeks and protruding eyes serving as key similarities to the lion.

Dogs have also had great influence from their devoting relationship and loyalty to man over history. One particular famed story credits a dog for saving the life of the future founding father of the Qing dynasty, Nurhaci. As the story goes, Nurhaci was fleeing the murder plot of General Li Chengliang as a young boy when his horse was shot down by the General’s men. In his escape, Nurhaci took refuge in a meadow of tall grass where he fell asleep. Suspecting that the boy was in the meadow, the General ordered his men to light the grass on fire. With the fire spreading, it was Nurhaci’s loyal companion that ran to a nearby river, soaked itself in water, and ran endless circles around the sleeping boy to keep him alive. Nurhaci awoke to find himself unscathed by the flames thanks to the tireless efforts of his dog, who passed away from exhaustion shortly after. Nurhaci never forgot this noble sacrifice by the dog and when he rose to power, he decreed that the killing of dogs, any consumption of their meat, or the wearing of its fur was strictly forbidden (Wei, 2005). This brave tale of loyalty and sacrifice is one that signifies the importance of man’s best friend.

Works Cited

Lu, Diana. “Celebrating Chinese New Year: Dogs in Ancient China.” Royal Ontario Museum, https://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/celebrating-chinese-new-year-dogs-in-ancient-china.

Dai, Wangyun. “7,000 Years of the Dog: A History of China's Canine Companions.” Sixth Tone, 15 Feb. 2018, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001742/7%2C000-years-of-the-dog-a-history-of-chinas-canine-companions.

Wei, Song. “The Attitude Towards and Application of Animals in Traditional Chinese Culture.” Michigan State University College of Law, 2005, https://www.animallaw.info/article/attitude-towards-and-application-animals-traditional-chinese-culture. Accessed 28 Oct. 2021.

“Dog Cage (Goulong).” Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/60013.

Tuan, Y.-F. (2016). Dominance & Affection: The Making of Pets. Yale University Press.

Schafer, E. H. (1963). III. Domestic Animals. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand, 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520341142-007